I recently came across research that’s been done over the past decade in the UK on the effectiveness of branding versus direct response ad campaigns. The researchers at the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising looked at about 1,000 award-winning campaigns. Some of what they concluded:

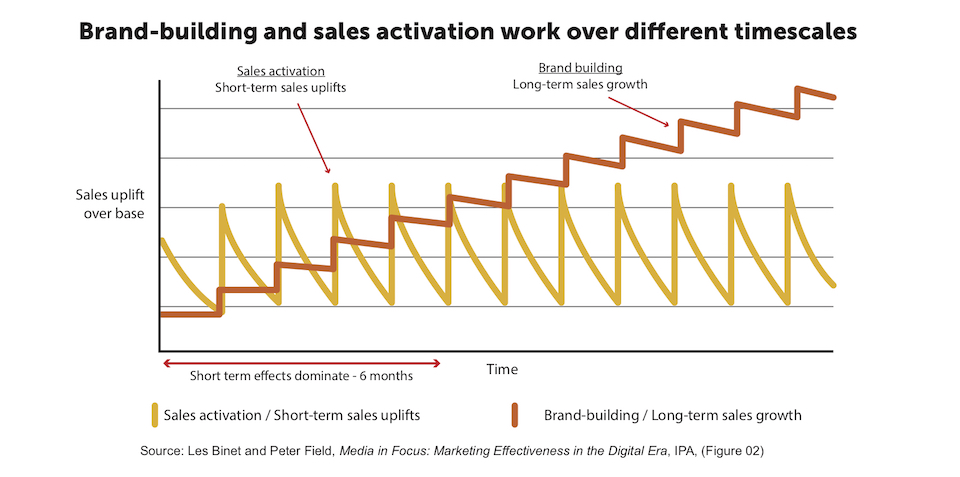

- Direct response (DR) campaigns (like email, direct mail, search advertising, etc.) drive the best short-term results, but branding campaigns are more effective in the long run

- The accumulation of multiple DR campaigns do not equal the impact of branding campaigns

- Creative/award-winning branding campaigns have greater impact, not surprisingly, than less memorable ones

- DR campaigns tend to increase volume of sales in the short run, but branding campaigns can impact the willingness of customers to pay more (higher profits)

- DR campaigns that use price (10% off!) as their offer hurt the price elasticity of customers

- The most effective DR campaigns are reason-based; the best branding campaigns are emotion-based.

- Branding campaigns typically take more than 6-12 months to have their greatest impact. They can still be increasing their effectiveness after 2-3 years. (Progressive’s “Flo” campaign has been going since 2008. The Marlboro Man was launched in the 1950s and ran for decades.)

- Optimal campaigns are branding with DR elements.

The recommendation of writers Les Binet and Peter Field is that in the long-run marketers should allocate roughly 60% of their budget to branding and 40% to DR efforts.

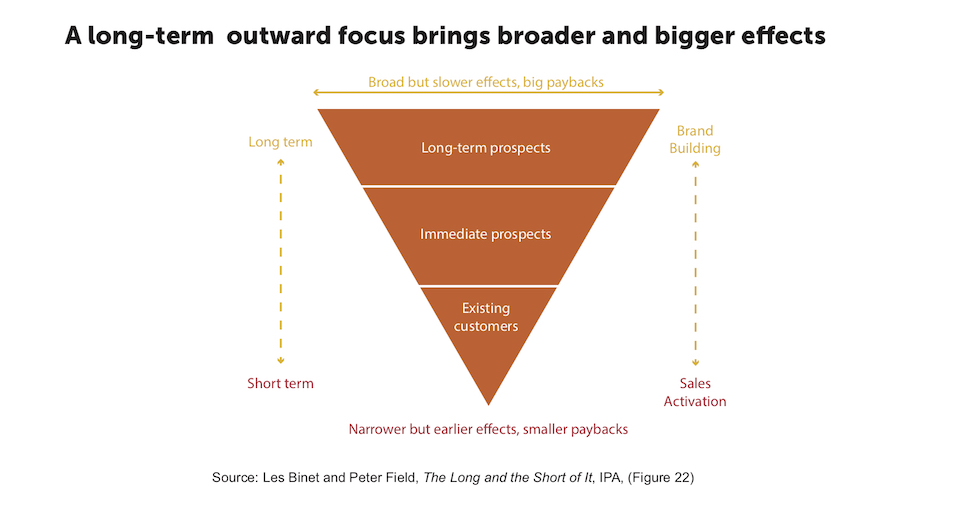

They did also say that it would be controversial that they found that advertising campaigns are far more effective, and cost effective, for new customer acquisition than getting more business from existing customers. That doesn’t entirely surprise me, though. It’s not the role of advertising to grow and build current accounts; customer experience is more important for that, and other tools like email updates and inside sales.

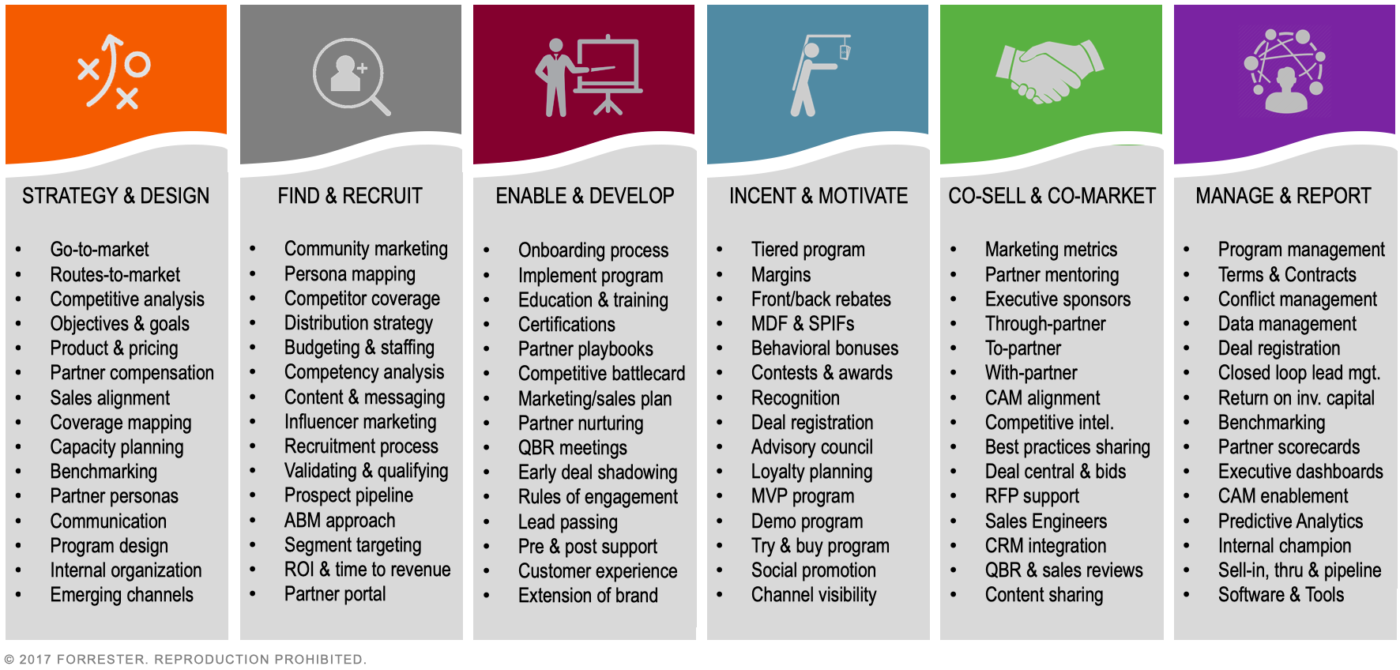

This graphic nicely illustrates their conclusion that the impact of branding efforts are cumulative and, ultimately, more effective.

Their balance of short- and long-term recommendations aligns very well with my Bullseye Marketing approach. This chart of theirs could have been a summary of my book.

By focusing on the Phase 1 and 2 programs of my Bullseye approach you’ll not only have quick wins that build buy-in, but you’ll also set the foundation for success with your long-term, Phase 3 branding efforts.

But if you started with just the branding programs, the likelihood is that you wouldn’t have many measurable results in the first 6-12 months, your leadership would lose confidence in marketing, and you wouldn’t have the budget or support for long-term success.

BTW, this work is based on B2C campaigns, which may be why they said that TV is especially impactful for emotion-driven branding campaigns. They are working on new research now that is specific to B2B.