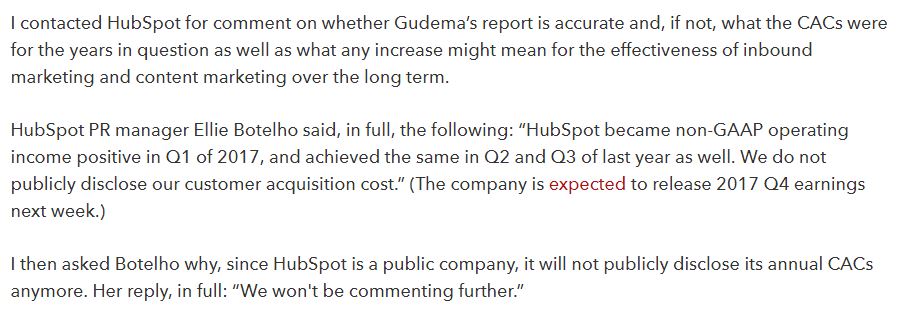

HubSpot is a public company. Their financial information is supposed to be shared with everyone. Why such selective communication of such good news?

Anyway, in a sense it doesn’t matter. The title of my original post was “Can HubSpot afford to do inbound marketing anymore? Can you?” It’s the second question that’s far more important.

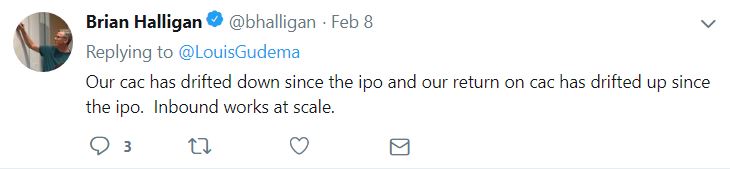

Note that each time Halligan says that inbound works “at scale”. HubSpot itself has spent tens of millions of dollars – maybe over $100 million — over the past dozen years producing content for inbound. Only very large companies, or VC-backed ones, can afford to do that (certainly not the SMBs that are HubSpot’s primary market). If that’s the scale that it takes these days for inbound to work in most industries, then my original observations on its dwindling effectiveness still hold.

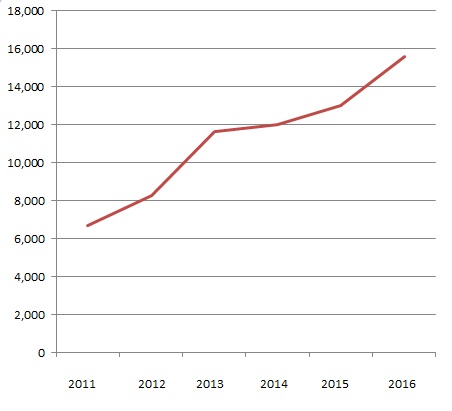

According to third party SEO tools (SpyFu, SEMrush, Ahrefs, Alexa.com) HubSpot every year gets the equivalent of tens of millions of dollars of paid search traffic to their site for free from their thousands of ranked pages, which have tens of thousands of external links to them. They could literally stop spending any money on new content and, since it’s so hard to displace a highly ranked page, they would continue to get millions of dollars of free traffic for a long time. That can be the long-term value of inbound (if that traffic also generates qualified leads).

HubSpot’s investment, and results, from inbound puts them in what I sometimes call “the marketing 1%”. In fact, they’re in the .1%; their site ranks in the top few hundred sites globally. That’s what investing tens of millions of dollars in content can produce over time.

But this won’t happen for many other companies. The three situations in which inbound may produce results today are:

- Your company is a traditional leader in your industry, possibly through a long-term content program, and has high domain authority

- You’re in a relatively new industry, little content has been produced yet and no one has established a leading content presence (maybe companies in AI were in that position in 2013, they certainly wouldn’t be today).

- You have a very large amount of money to spend on your inbound program, either because you’re large enough or are VC funded.

Secondly, as I mentioned in an article for growth stage VC firm OpenView, HubSpot has virtually re-defined inbound out of existence. The original idea of inbound was totally anti-advertising. In the second edition (2014) of their Inbound Marketing book, Halligan and HubSpot co-founder and CTO Dharmesh Shah wrote about their defining of inbound marketing: “Inbound was about pulling people in by sharing relevant information, creating useful content, and generally being helpful.”

And they continued their disdain for traditional, “outbound” marketing: “Now, raise your hand if you love getting cold calls from eager salespeople during dinner. Or spam e-mails with irrelevant offers in your inbox. How about popup ads when you’re trying to read an article on the Internet?”

But HubSpot now sells ad management software. So on its website it now says things like, “A common misconception is that inbound marketing and display advertising are simply incompatible. Increasingly, however, marketers are combining the best techniques from both to maximize their reach and find qualified potential customers.” I don’t know how that misconception arose.

I won’t go through everything in that OpenView article here, but check it out. In it, I go into much more detail on why the inbound marketing strategy launched in 2006 just doesn’t work for most companies today.

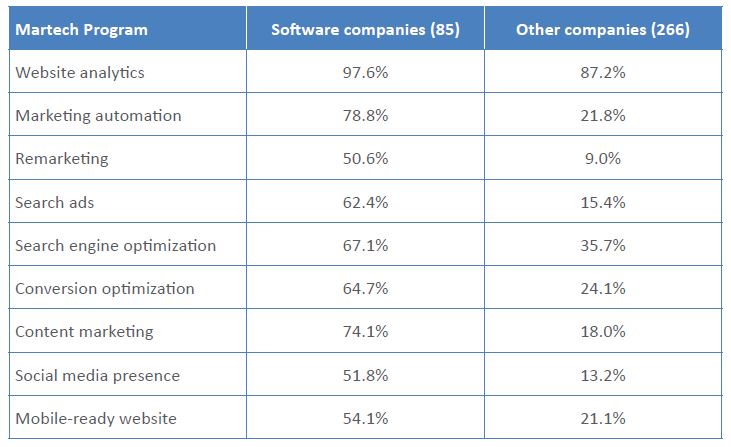

The reality is most B2B companies outside of the software industry are still doing very little marketing. I studied hundreds of them and found this adoption of marketing programs.