Last week I attended a panel on “The Future of Small, Private Colleges” at McLane Middleton, a New England law firm. One of the panelists was the current president of Montserrat College of Art, a 400-student school north of Boston, Dr. Kurt Steinberg. He had a lot of great insights into the crisis in higher ed which, to a significant degree, is a failure of marketing.

He divided small, private colleges into two major categories: specialty schools and general, liberal arts schools. Specialty schools, such as those focusing on art, engineering, or business, are actually growing. It’s the small liberal arts colleges that are shrinking and dying.

Dr. Steinberg understands that they need to market Montserrat as a small, non-urban arts college. Students who want to go there wouldn’t like Pratt with 4,500 students in New York City, and vice versa.

In general specialization is a good business strategy. Saying that you’re good at everything is rarely a convincing or compelling proposition, but saying that you’re an expert at one thing can be. Who wants to hire the proverbial “jack of all trades, and master of none”?

Jay McBain, from Forrester, made a similar point in my interview with him on my podcast, “Ten years ago we used to build these partner programs that try to get you to go after one of the 27 verticals. ‘Go read healthcare, high tech, HIPAA, and become a health care expert.’ Today it’s a sub-industry play. There’s 297 sub-industries below those 27 majors. And instead of just being a health care expert, be a midsize clinic with 50 doctors specialist.”

I think that this was one of the reasons that Newbury College in Brookline, MA, closed last month. They had both a strong culinary arts program and a liberal arts division. The Bureau of Labor Statistics says, “Employment of chefs and head cooks is projected to grow 10 percent from 2016 to 2026, faster than the average for all occupations.” Newbury could have doubled down on being a culinary arts school, but instead they presented a vague message (their website is still online): “Newbury College provides a meaningful education inside and outside of the classroom. Founded in 1962, Newbury has always sought to provide students with a career-oriented, experiential education. Beyond academics, Newbury’s mission is to encourage lifelong-learning and engaged, socially-responsible citizenship.” It didn’t work.

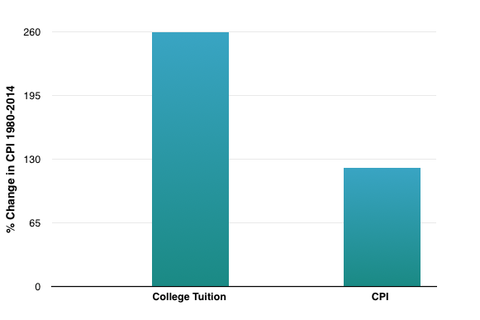

Another problem for liberal arts colleges, which Dr. Steinberg didn’t touch on, is that for many families these liberal arts colleges have priced themselves out of the market. College tuition has risen twice as fast as inflation in general. Many parents and students want to now know that there’s a paying job at the other side of that quarter million dollar investment.

And the customer is changing. A growing proportion of students are first generation in their family to attend, or black or Hispanic; many may be looking for a different experience, or different services, than fourth generation white students.

And the competition is changing. Dr. Steinberg also noted that larger universities are getting better at creating and promoting specializations within their large and diverse offerings. With honors colleges and special dorms, they can cater to the needs of students looking for more focus. I still remember touring the University of Maryland (40,500 students) with my daughter; the excellent student guide at one point said, “You’ll find your small college in a large university, but you won’t find a large university at small college.” Some students are attending online programs, too, although that’s still a small number at the undergraduate level.

In my opinion, all of these are marketing issues. The colleges that understand their rapidly changing market, adjust their product, and promote it well, can survive and even thrive.