This is part of chapter 22 from Louis Gudema’s Bullseye Marketing book, which is available on Amazon.

“Without data, you’re just another person with an opinion.” -W. Edwards Deming

If you’re new to digital marketing, you’ll likely be amazed at the amount of data that the tools collect and the analytics that they provide for you to optimize their performance.

In fact, it can quickly overwhelm you.

Consider just a few of the sources of data:

- website usage data from Google Analytics

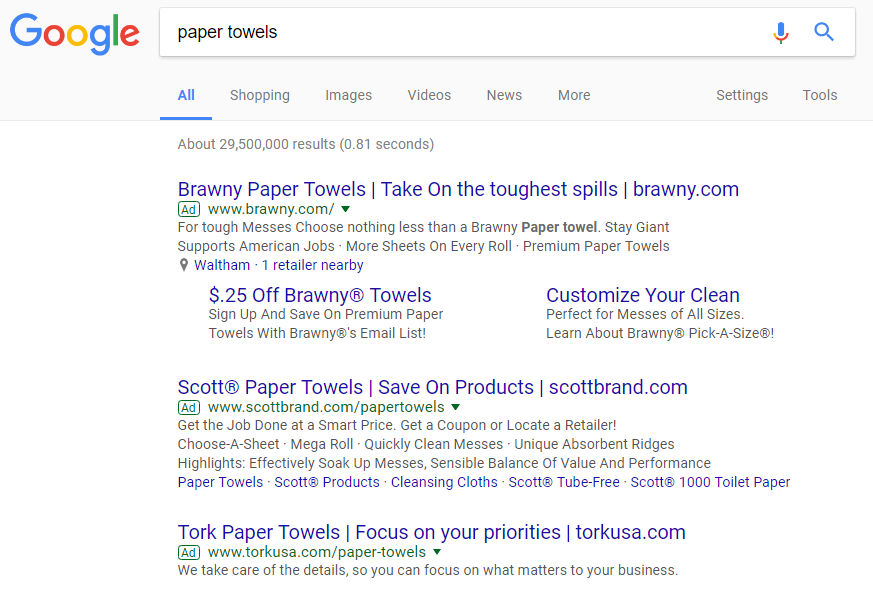

- search ad data from Google AdWords and Bing

- email performance data

- landing page conversion data

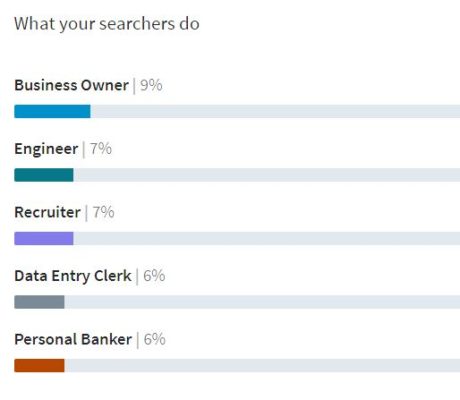

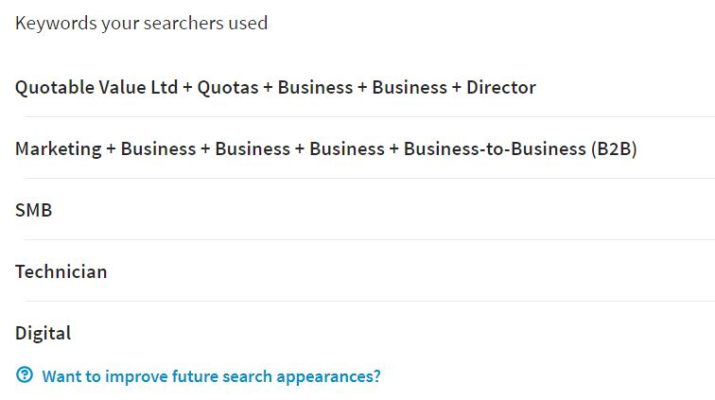

- social media channel analytics

- ecommerce data

- cross-channel analytics and attribution models

- predictive analytics based on the above, and possibly thousands of third-party data sources.

Now add in data from traditional marketing channels such as direct mail, call centers, print, TV and radio.

To use this tsunami of data and analytics tools effectively you need to focus on what’s important and how to achieve it.

Campaign versus business goals

For most companies the primary business goals will be tied to top line revenue such as increases in qualified leads, opportunities and sales. Those are things that CEOs and CFOs usually care about.

To achieve those, though, as marketers you’ll also have campaign metrics that you’re optimizing, such as conversion rates and website page views. The c-suite likely won’t be very interested in those, and they shouldn’t be.

Consider, for example, the hierarchy of email marketing metrics:

- Increased email opens and shares

- Increased traffic to your website from email

- More qualified leads from that email traffic

- Increased revenue from leads that originated from email

The first two are campaign goals, the last two are business goals.

Increased email opens may indicate you have better Subject lines and content, and you’re building a strong following for your emails, but if that doesn’t produce more traffic to your website then perhaps you don’t have enough, or the right, calls to action in the emails.

If the increased traffic doesn’t produce more qualified leads then you, again, may have an issue with your offers or calls to action, or the website conversion experience.

If you’re getting more qualified leads but that doesn’t produce a good increase in revenue, then you may have an issue with the handoff of leads from marketing to sales, or the sales team may not have the content it needs to close the deals.

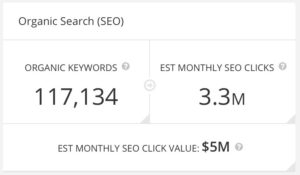

Or consider the hierarchy of search engine optimization metrics:

- Higher rankings on search results pages

- Increased organic search traffic to your website

- More qualified leads from search traffic

- Increased revenue from leads that originated in organic search

If your improved rankings aren’t generating more traffic, then either you aren’t optimizing the right pages or you need to create more content that customers are interested in. (This could also suggest a problem with your brand. Consider this situation: a startup company achieves the #2 ranking but is sandwiched between the top two market leaders with 70% market share between them. Few people have heard of the startup so even with a high ranking it’s not getting many clicks.)

If increased organic search traffic isn’t generating many more qualified leads then, again, you may not be ranking for the right content, or your website conversion experience may be deficient.

Each of these is important, but the first two are campaign goals that mainly marketers will care about. The last two are business goals and can be improved similar to how you improved them in your email campaigns.

In the process of using your tools you’ll have countless opportunities to optimize results. The important thing is to stay focused on what really is driving business results.

How to use data

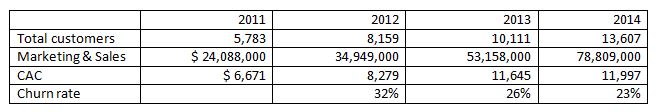

At the top level you may have goals for your company’s growth: you want to grow 5, 10, 20 or whatever percent in the next year. (People who write down their goals tend to be more successful in reaching them.)

With those sales goals in hand you can then work backwards to figure out your marketing goals and plans. Create an upside-down funnel:

- What is your sales team’s close rate? If your sales team closes one in three proposals, then they need three times as many opportunities as final sales. What percentage of opportunities is marketing responsible for generating, and what percentage is sales responsible for?

- Continue that calculation back through your funnel:

- How many of your sales qualified leads become opportunities?

- How many of your marketing qualified leads become sales qualified leads?

- How many new leads are qualified?

- How many new marketing generated contacts become leads?

From this data you should be able to determine how many new contacts and leads marketing needs to generate to hit corporate sales goals. (These may vary by product or offering, too. Or deal size.)

You can make a similar calculation for ecommerce sites, and for B2C and retail companies.

Once you have these target funnel numbers you can work on the programs that will generate those new contacts and leads, move them through the pipeline, and help sales close them. Use data and analytics to constantly be improving channels and campaigns.

You may start with a hypothesis: Email generated X new qualified leads last year. We need X plus 25% from email this year. We can achieve that by (1) increasing our list size, (2) changing the frequency of the emails, (3) having more effective offers and calls to action, (4) improving the landing page and conversion experience, or (5) some combination of those and other factors (subject lines, email copy, etc.). Then you can test each of these to reach your results.

Sometimes you will find that a particular channel or campaign simply isn’t going to produce the results that you need. That is valuable information, too; everything is an experiment. Thomas Edison’s team tested 10,000 materials before finding the one that would work for the light bulb filament. He said, “I have not failed. I have just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

Persist. Keep experimenting. Keep track of everything. And if you have a valuable product or service, you will find the best channels for generating new business for it.

Marketing attribution

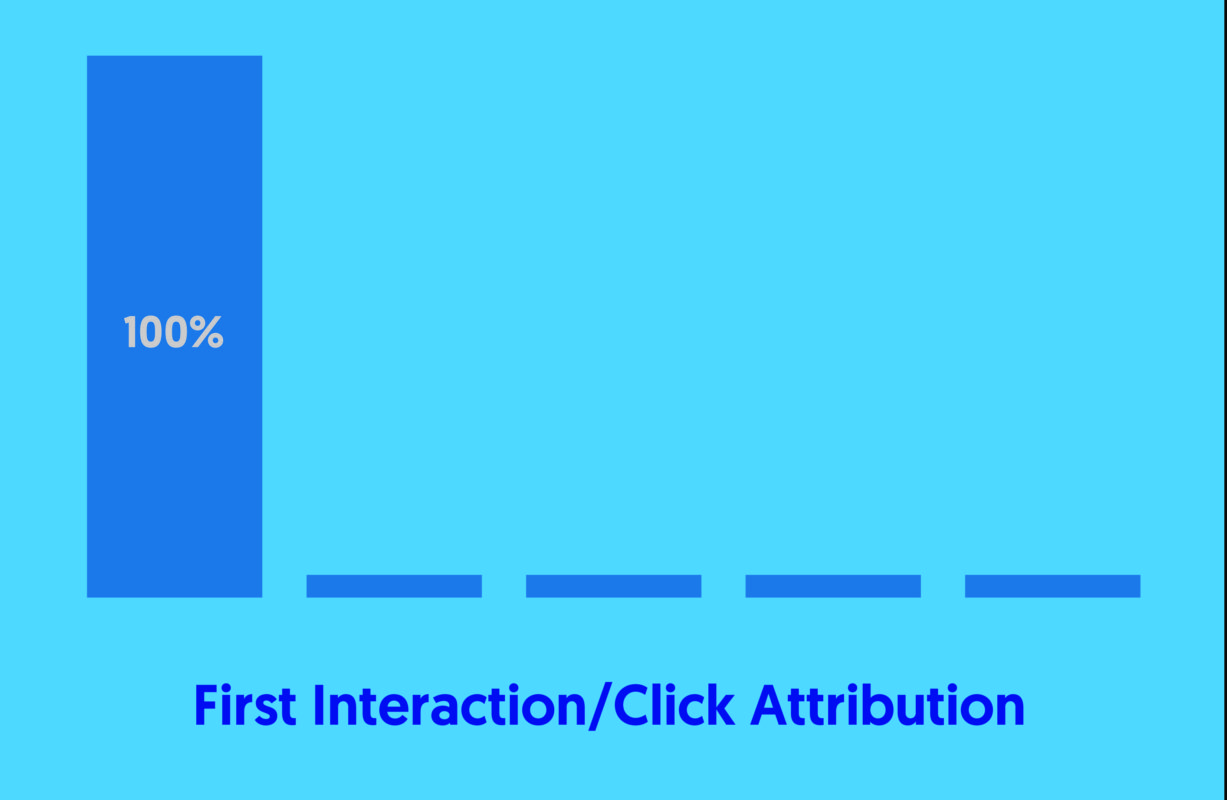

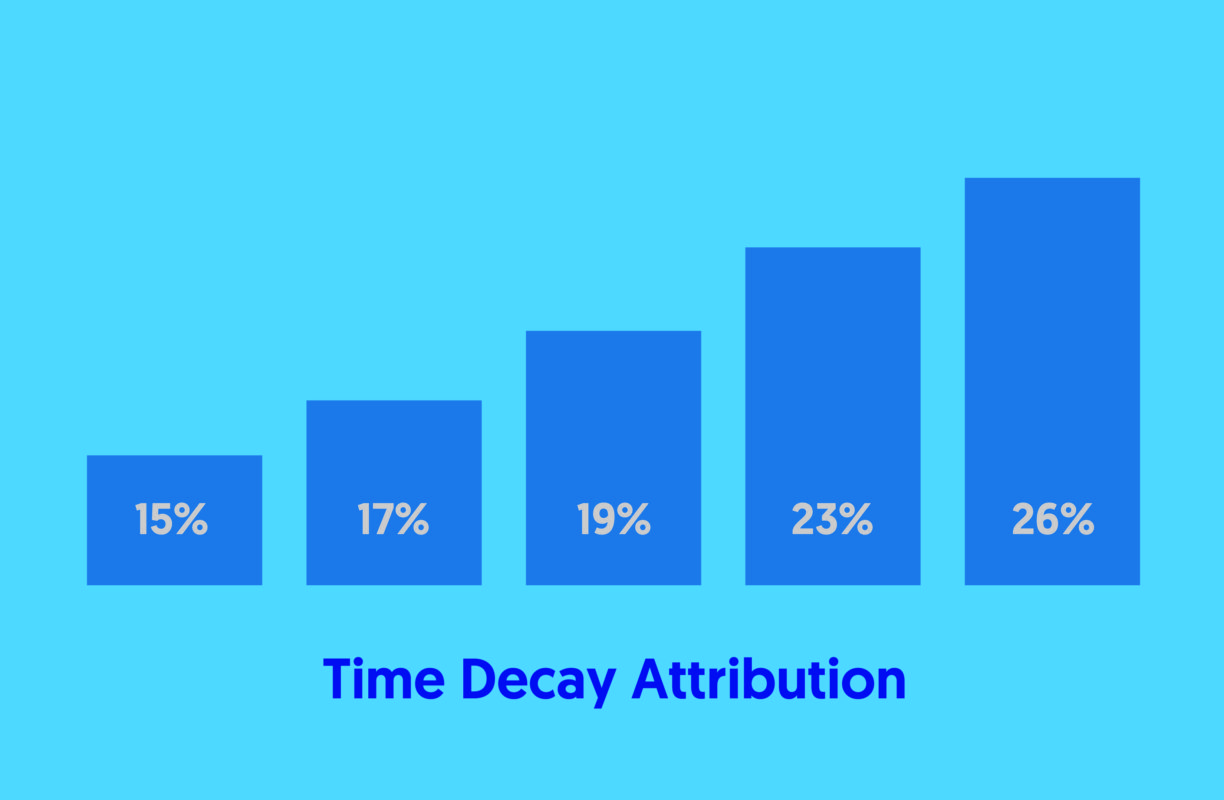

In this omni-channel world where you need to connect with your customers throughout their buying experience, attribution models help you determine the relative importance of the various marketing channels toward the final sale.

There are many marketing attribution models. Let’s look at the pros and cons of three.

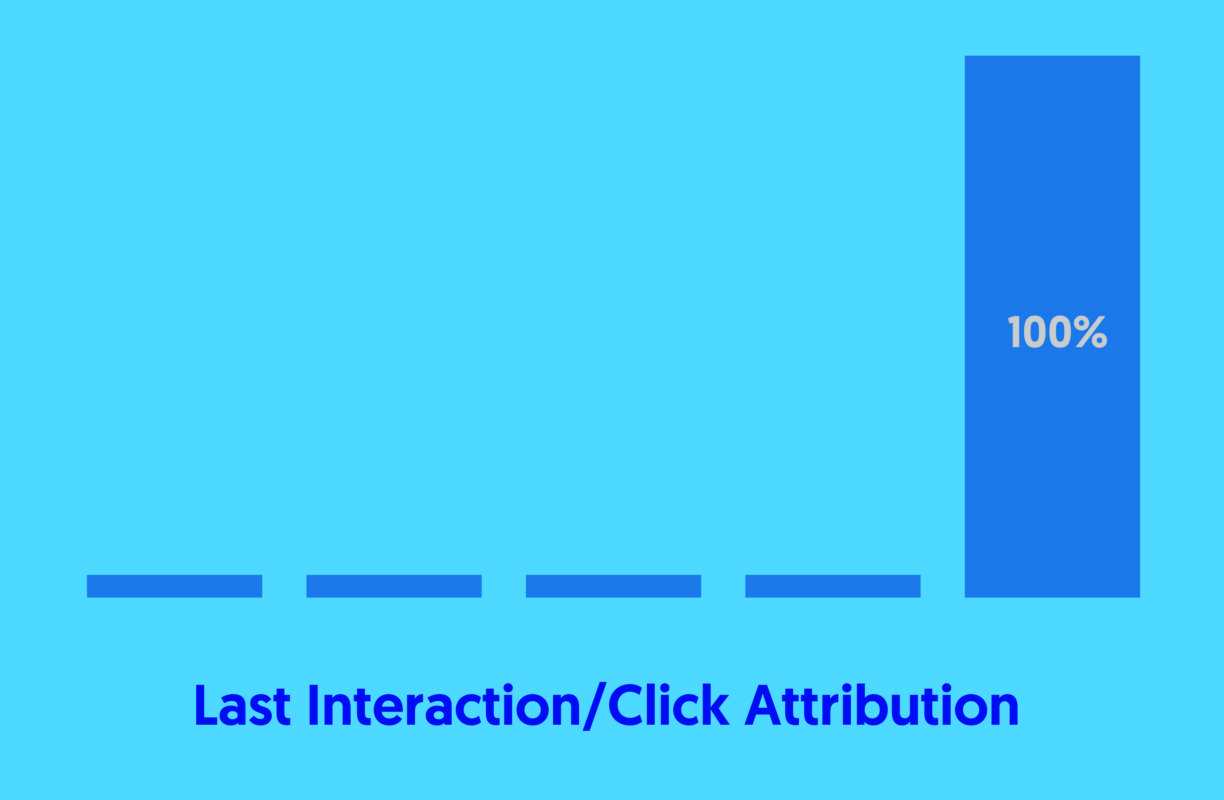

Last click/interaction

Let’s say that a person clicks on one of your search ads, comes to your website, and buys something. With the last click model, you give 100% credit for the sale to the search ads.

However, this is probably not very accurate. The person may have had several interactions with your brand before actually buying. They may have visited the website a few times, read reviews of your products on review sites, watched a few videos on YouTube, and so on. They may have been interested in your product for years. But with the last click model, none of that counts.