I recently read Bad Blood, the book about charismatic sociopath Elizabeth Holmes and her medical device startup, Theranos. Bill Gates entitled his review, “I couldn’t put down this thriller with a tragic ending.” It is, indeed, a page turner.

In case you haven’t heard of Holmes or Theranos, she dropped out of Stanford in 2003 after one year to start the company. Her promise was to revolutionize medical diagnostics by creating a device that could perform hundreds of blood tests on just a few drops of blood from a finger tip; drawing blood from veins would be unnecessary. But, as Wall Street Journal reporter and Bad Blood book author John Carreyou explains at one point, that was probably never even physically possible: the blood from finger tips can’t provide the same information for tests that blood from veins does.

And very likely Holmes’ goal really was personal wealth and fame. She considered herself (and was often called in articles) “the next Steve Jobs” and imitated Jobs and Apple in many ways, including wearing his trademark black turtlenecks to work. At company meetings she would sometimes say, “If you don’t think that what we’re creating is the most important invention in the history of humanity, then you should leave right now.” Really. Batshit crazy.

Through a combination of connections, charm, and charisma, she ultimately was able to raise close to a billion dollars for the company. Its valuation rose to $9 billion and, since she retained ownership of over half of it, she was listed on the 2016 Forbes 400 as worth $4.5 billion.

But a year later her net worth was $0.

By then the astonishing number of corporate lies that had led to the company’s rise had been exposed by Carryou, the WSJ, and others, the federal government had withdrawn authorization for use of their technology and labs, and the house of cards had collapsed.

A few takeaways:

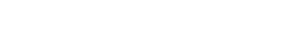

- A free press is SO important. While many people in Silicon Valley and elsewhere had their doubts about Holmes and Theranos, it wasn’t until the WSJ published their story that they made their doubts public. This is similar to what happened recently with the rapper R. Kelly, who got away with decades of sexual harassment that was well known in the music industry until Lifetime ran a several part documentary on him.

And anonymous sources, in the hands of reputable journalists and publications, are necessary. Theranos had iron-clad non-disclosures for its employees and was highly litigious, using the law firm of David Boies to threaten and intimidate employees who might have spoken out. The parents of one young employee – who was not even sued by Theranos – spent $400,000 on lawyers to deflect the attacks of Theranos and Boies.

BUT, an uncritical free press also fueled Theranos’ rise earlier on. You have people like Jim Cramer on his Mad Money show giving Holmes a platform to respond to the initial WSJ articles, and then later interviewing Carryou and tutt-tutting Holmes.

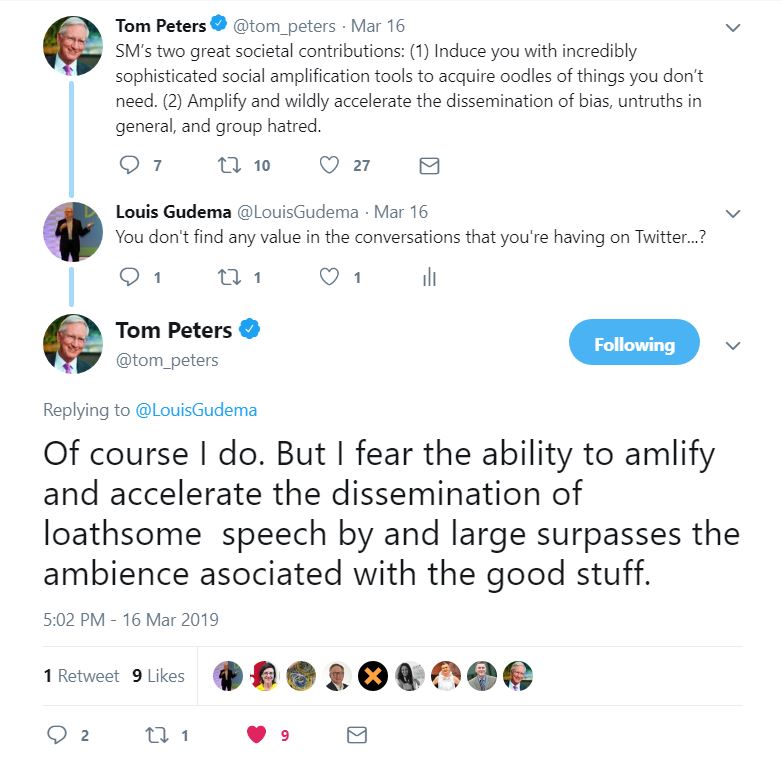

- The charisma trap. Holmes was apparently quite charismatic in person and could convince people that – despite little relevant industry experience – she could do the impossible. Once she had former Secretary of State George Schultz on her board, she could parlay that into a board full of esteemed elder statesmen (Henry Kissinger, Sam Nunn, James Mattis, etc.). Indeed, most of her initial investors and board members were men over 70. None had medtech experience. (Apparently the Silicon Valley medtech VCs were for the most part not convinced and did not invest.)

On one level this is a story of startup board negligence, but since Holmes retained ownership of over half the shares the board was little more than a figurehead anyway. There was no way that they could have initiated an independent investigation of her or the company’s practices once the stories broke. When one board member started to express doubts, he was kicked off the board.

But kudos to WSJ owner Rupert Murdoch who was, before his paper broke the story, the largest investor in Theranos. Despite having put $125 million into the company, he refused Holmes when she asked him to squash what she said was going to be an inaccurate article in the WSJ. He probably gets, and brushes off, those requests all the time.

- How could so many people – hundreds – stay at a company that was conducting medical fraud? Ultimately Theranos had to void over one million tests it had performed. I know a job is important, but come on, this wasn’t a game or productivity app: we’re talking about peoples’ lives. That is just shameful. Kudos to the employees who quit and, even more so, to those that dropped a dime.

It’s a fascinating book. At first it’s kind of like watching a corporate train wreck. Time after time you see someone get close to the truth only to be told to stay in their lane, or that a partnership with Theranos was too important to stop. Ultimately you begin to wonder how it’s all going to be brought down. And the final quarter of the book — the story of how Holmes, Theranos, and Boies tried to stop the truth from ever getting out – is quite a gripping tale in itself.